Not so long ago – or maybe a lifetime ago, I can never tell – I couldn’t really work out what I should do with my life. I found myself paralysed with indecision. I looked around me and just about everybody else seemed to know exactly what they were up to. I had no idea. My problem was that I couldn’t seem to focus on just one thing. There were too many things

I was interested in (textile design, furniture design, children’s products, animation, film, scriptwriting, book illustration, ceramics etc) – I thought choosing one would mean missing out on all the others.

So I flitted about, not particularly choosing anything, with the result that

I missed out on everything. I had always hoped that I might be discovered in a supermarket, or maybe at a bus stop – I had heard that this sometimes happened to people who then went on to lead hugely successful lives.

It slowly dawned on me that it was impossible to be discovered for something if nobody could see what they were meant to be discovering, and that led back to the whole problem of choosing something. Then one day when I found myself very desperate and quite panicky, I went to see the mother of a school friend – she was a very successful fashion designer and I always found her inspiring to talk to. She suggested that I send my portfolio to her business manager, to see if she had any advice or even the vaguest idea about what I should be doing. It seemed worth a try.

The business manager said: it seems to me, if Lauren is interested in making a film or animated series and wants to see her characters licensed and has ambitions to design a range of children’s products or furniture, then maybe she should write a children’s picture book.

The author when guinea pigs were a priority.

I could see what she meant. I was not technically qualified to do any of the things I wanted to do and I had no money to just go ahead and set something up on my own. I needed to prove that I could come up with strong characters, create a world for them, draw and also design. Perhaps because this advice was given to me by someone successful, perhaps because I was hearing it when I was ready to listen, perhaps because it came from a total stranger, I took it on board.

I had made attempts at writing picture books some years before – my motivation had mainly been necessity since it was near impossible to get work as an illustrator of other people’s words and few publishers seemed keen to take a chance on someone with no track record. However, it was also near impossible to get anyone interested in taking me on as an illustrator of my own words. I vividly remember showing my story ideas to publishers but they always wanted me to make them more like this and less like that. They showed me examples of successful books, sometimes they even read them out loud – this I found both bewildering and vaguely embarrassing. However, I always listened, went away and tried again. The results were not good; if my writing wasn’t up to much before, then it was certainly a great deal worse after. But what I did learn was something very important indeed: there is no formula. Only one person can write The Very Hungry Caterpillar (or indeed any other book which has already been written). In other words, it is pointless trying to imitate and it will be somewhat mediocre if you do.

SUCCESS!

When I embarked on Clarice Bean, That’s Me, I think I sort of tricked myself into writing something personal and different. My aim was to create something that might eventually become a film, and this somehow liberated me from trying to write the perfect picture book. I stopped writing to a formula and instead wrote about something I was interested in, with the result that I stumbled upon my own way of writing.

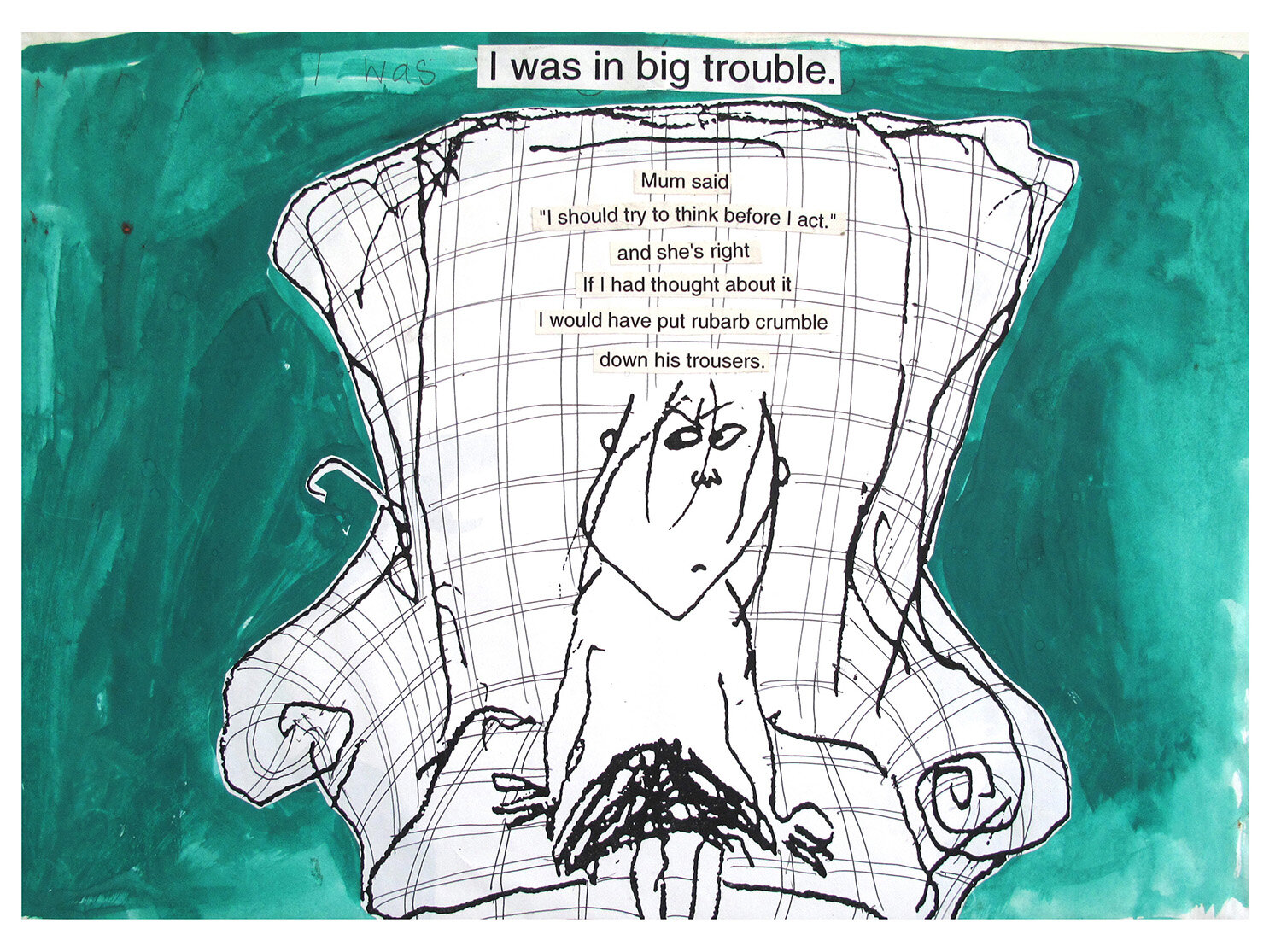

I just started writing down anything that came into my head. And then

I drew a bit. I just sort of started writing and drawing at the same time.

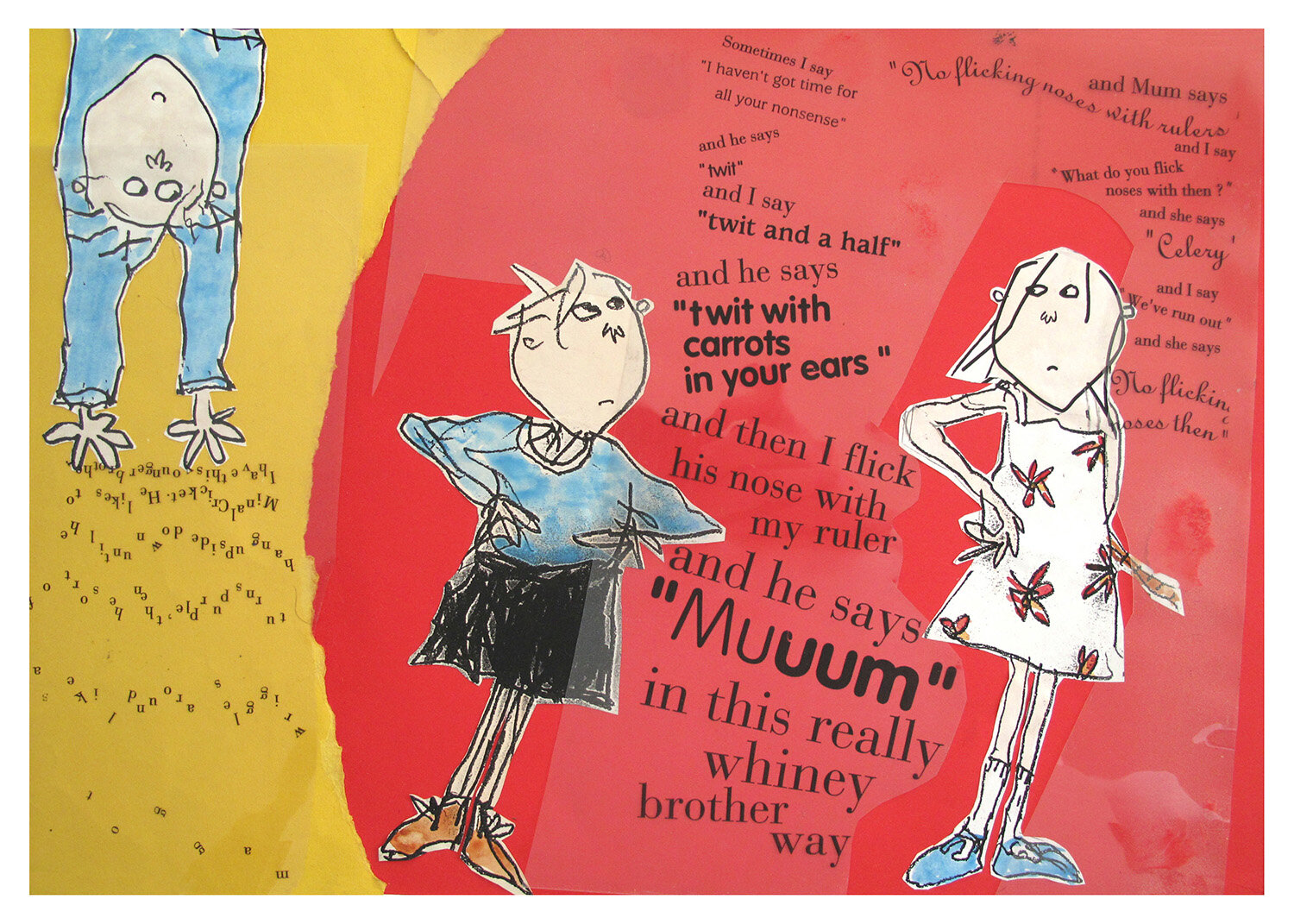

As I went on the words started weaving around the figures and sort of became part of the pictures. I came up with lots of characters because

I was imagining the story as a film or TV series and I thought it would be an advantage to have a big cast.

I had no idea what the story was about – it didn’t seem to matter – I just kept writing. All the words were spoken by a child, a girl of perhaps seven. She spoke out of the book as if she was telling the reader all about her family, uninterrupted, unedited. Everything we learn about her family is filtered through her – what she says isn’t necessarily completely accurate, it’s just her take on things.

I had quite a clear idea of the girl’s personality – she wasn’t based on anyone I knew but she seemed very real to me. As I did more drawings, she evolved, became rounder and less scribbly.

The character I had in mind slowly developed through trial and error.

When I had written everything I wanted to write, I put the pages in some sort of order – just the text without the pictures. I typed it up on a friend’s computer – I didn’t have one of my own. The result wasn’t so much a story with a plot, as a series of illustrated anecdotes told by a child.

I thought I would use different typefaces for each person because it would mean that just by looking at the picture you could hear what kind of voice they had:

Then I did six colour double page spreads – all had the text positioned. Some I did by cutting up type and gluing it in place. Others I worked on with a graphic designer friend who knew how to typeset.

Although I had studied illustration for a year, alarmingly I had no knowledge of even the most basic things. So here you see the text sometimes falls into the gutter as does the image. This would make it impossible to read. The placement of the type is far too complicated but that I think is no bad thing – better to get the idea across and pare it back later.

It was important for me to show how the text worked with the pictures because the type itself becomes part of the illustration.

I TOOK MY BOOK IDEA to New York and showed it to a publisher who published unconventional picture books – next to those, my book looked quite tame. She said, “No – too English.” (which is funny since people often imagine that I am American).

New York City.

I came back to London and I made an appointment to see the UK publisher that at the time I most wanted to be published by. They said, ‘This book will never be published.’ They suggested ways to change it to make it publishable but their suggestions were very radical and had nothing to do with what I was trying to say. I then showed it to lots more publishers; just about all of them felt it was a problem to have the story told in the first person. Many of them thought it was confusing to have the words moving about within the pictures, everyone felt it needed more of a point to it. I was advised to get rid of the pictures, or the text, and certainly the moving about words. I decided not to – it just didn’t feel like the right thing to do.

Years of failure had taught me a lot. Even though every single publisher was saying “no”, I recognised from all the previous years of “no’s” that there was a difference – they were saying “no” but they slightly wanted to say “yes!” I could also see that compared to anything I had done before this was not bad – nothing about it was making me actually squirm

(I always find this a good test). Luckily I had already reached an all-time financial low several years earlier and although being broke was in no way nice, I knew that I could survive.

In this time I had two pieces of good luck. One was that I met a publisher called Suzanne Carnell, then at Kingfisher. She thought Clarice Bean had potential and offered to edit it for me. What she did was to rearrange the pages so that it became a book about a quest for peace and quiet. She also advised writing an extra piece for the ending – I did as she suggested – she was right, it pulled the book together. Unfortunately, Kingfisher couldn’t get an American co-publisher for the book and without that they felt it was impossible to publish.

The second piece of luck was getting an agent. I had been warned that getting an agent would be near impossible; I think I just got to see the right person at the right agency on the right day (she had only recently started taking on children’s authors and maybe this helped). I handed the book to her and then I waited. Nothing happened with Clarice Bean for about four more years, in which time my agent had moved on but my career had not.

In the meantime...

I started a lampshade-designing company with a friend. It was called Chandeliers for the People. I also got a job as an artist’s assistant, and then another as a receptionist in a graphic design studio. I also wrote another book, a much simpler one called I Want A Pet which was told in the same sort of first person chatty style as Clarice Bean but it featured lots of animals (I was aware that books with animals are popular) and it had very simple illustrations and a very pared back narrative and no intergrated text. I sent this to my agent and I got on with other things. Finally, in 1998, Frances Lincoln said “yes” to I Want A Pet and it was published in the spring of 1999. A few months later Orchard Books said “yes” to Clarice Bean, That’s Me and it was published in July of the same year.

Of course, things had to

be tweaked and adapted

The type, for instance, was too chaotic and tricky to read, but I wasn’t asked to make any fundamental changes that I couldn’t live with. I had found a sympathetic and exciting editor in Francesca Dow – who managed to improve my work without deconstructing it – and I had found a supportive publisher in Orchard Books.

Clarice Bean, That’s Me is probably my favourite of the books I have written – partly because it is the book that got me where I am now and partly because it reminds me how determined I had to be to get it published – it’s good to remember that it wasn’t easy that things often aren’t easy but they can turn out in the end if you don’t give up.

Five Things about Clarice Bean

I called her Clarice because…

I didn’t know a single actual person called Clarice. I made her middle name Bean because I thought her parents were quite unconventional and might be the sort of people to give their child an unusual combination of names.

When the book was published...

Orchard Books got a phone call from a lady living in Putney –

she said, ‘I am Clarice Bean.’

Clarice started off…

as a seven year old in the picture books but got progressively older in the novels. By the time I wrote Clarice Bean, Don’t Look Now,

I imagined her to be about eleven.

She is my favourite character...

to write about because she can talk about anything she feels like talking about.

In the first handwritten account...

the family dog was called Clement. But, when I typed it,

I accidentally missed out the ‘L’ and he became Cement.

This is a much better name for a dog, so I left it.

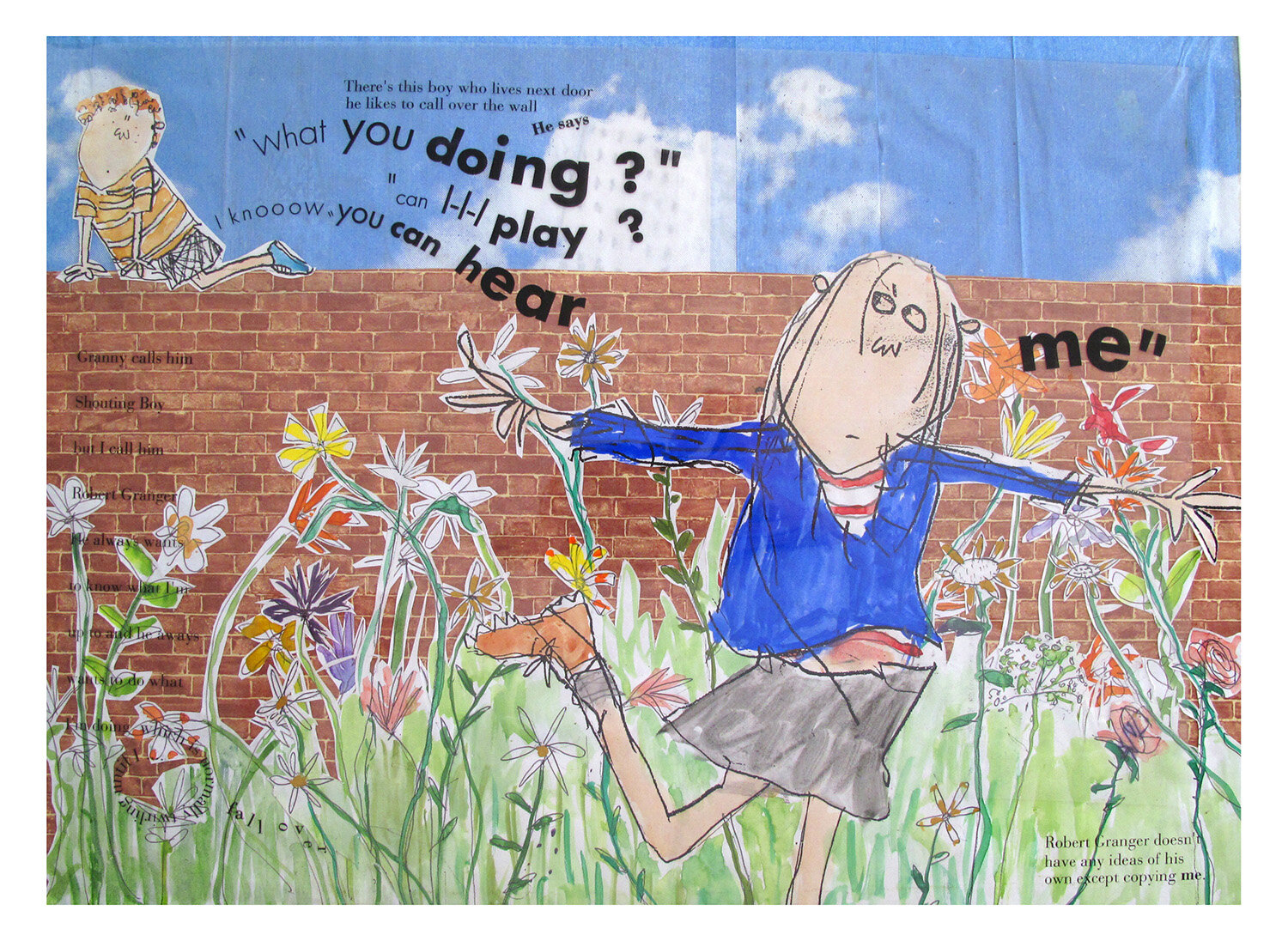

Many of the characters are based on people I know.

Robert Granger is based on my real-life neighbour at the time of writing the book. He was called William and must have been about six or seven. He wore little shorts (which were a bit small for him) and he owned a guinea pig. Most days it seemed he would sit on top of his garden wall shouting across at the little girl who lived next door. He would shout her name over and over again. I was three floors up so I could often see her hiding behind a tree and pretending not to hear him – which was impossible because he had a very loud voice. My flatmate and I called him Shouting Boy.

Clarice Bean’s Mum was sort of

a mish-mash of several people’s mothers; one a tightrope walker, one a magician’s assistant and the other was just one of those very capable people who never seemed fazed by anything.

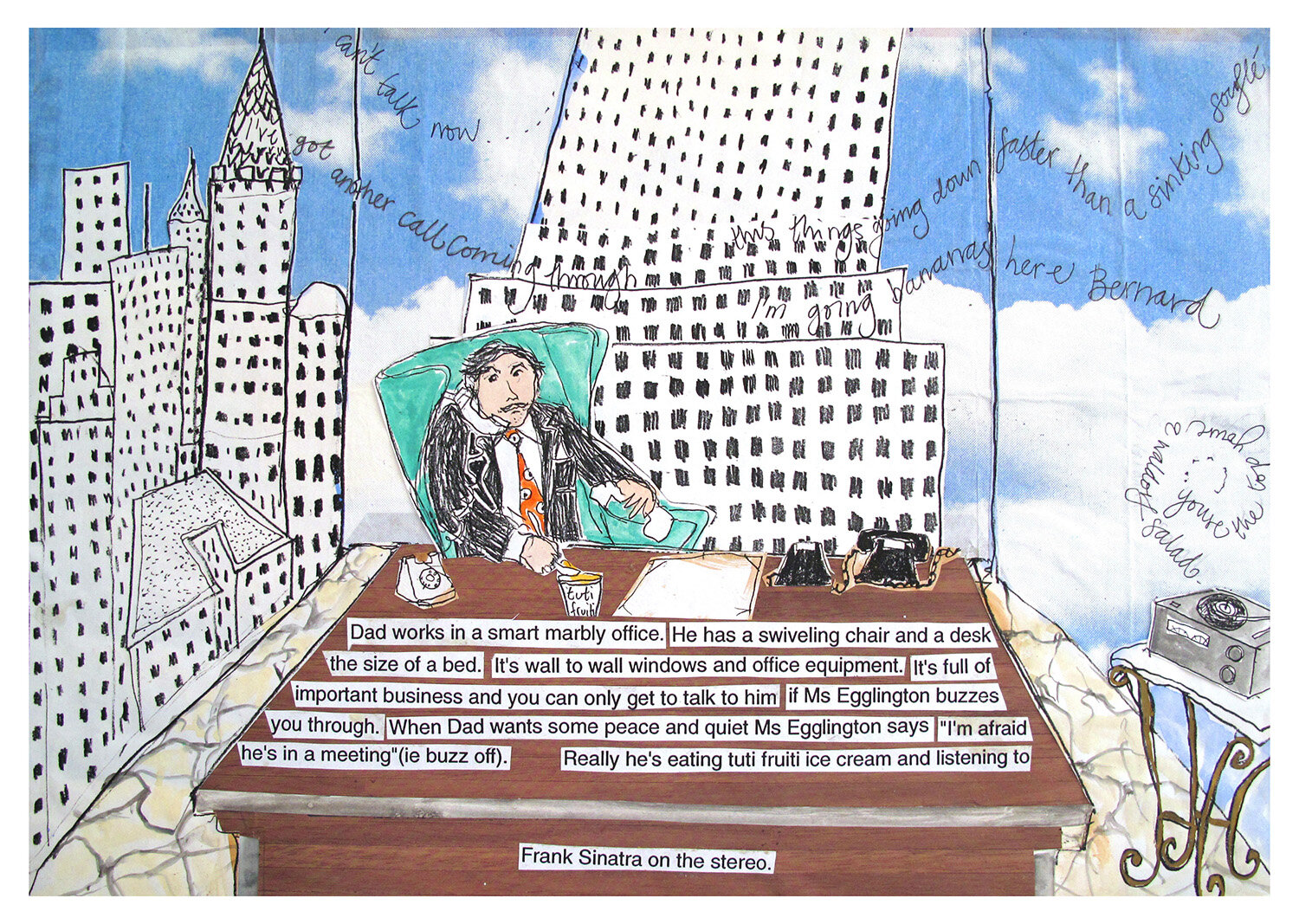

Clarice Bean’s Dad was partly based on a friend’s father who

I always thought was rather glamorous and important.

I think of CB’s dad as American, this explains why they have family in New York. People often ask me why he has a moustache when moustaches aren’t really in fashion these days. The answer is because

I find it very hard to draw men – they just seem to look more ‘manly’ if they have facial hair.

In the same way I often give my women characters long eyelashes to make them more feminine.

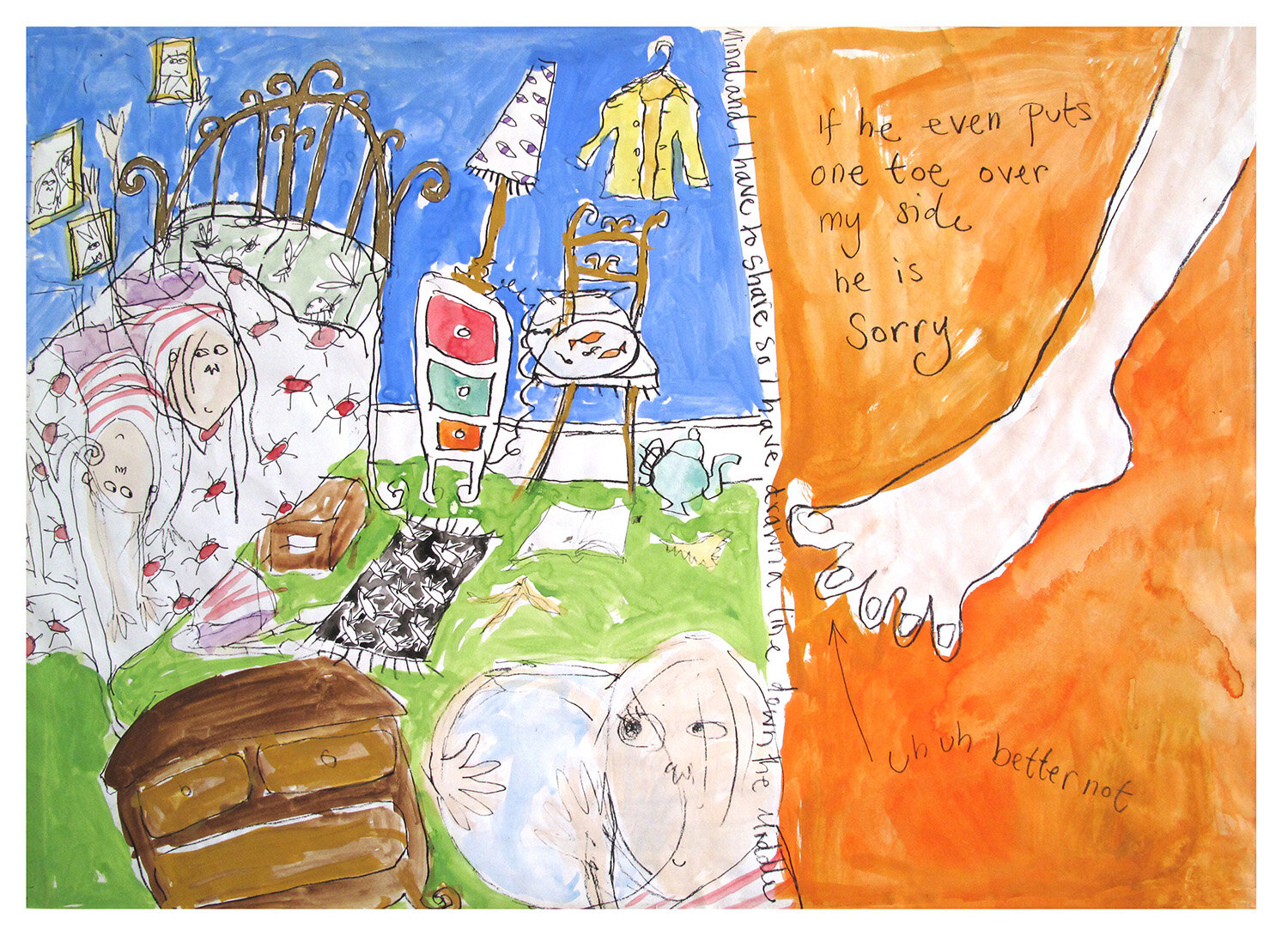

Minal Cricket is slightly based on my little sister. When we were small we had to share a room.

I hated this because she was very untidy and her toys always spread over to my side of the room. I was always shunting her stuff over an invisible halfway line. We get on much better now.